Glider was one of my favorite Mac shareware games back in the day, so I have a soft spot for Richard's retrospective on the series.

SimCity had just been released, so he tried Maxis -- no response. Then he tried Casady & Greene, whose ads -- for the games Crystal Quest and Sky Shadow -- he had seen in Macworld magazine. They liked what they saw. Calhoun would make a color version of Glider, with more rooms; they would publish the game and give him a color Macintosh for development. He offers a simple comment: “What a deal.”

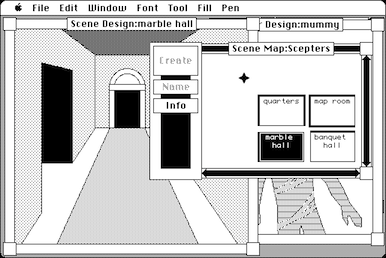

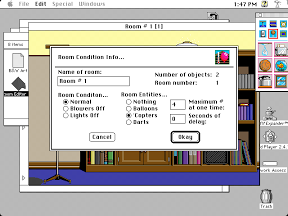

The demand for more rooms struck another lightbulb in Calhoun’s head. Creating rooms for the house was a tedious process in which objects were laid out blindly -- everything was hard-coded and testing changes was slow. So he thought to create a “room” editor, which would let him create rooms via a graphical user interface and test them with a simple modification to the start point.

But he didn’t keep the editor to himself. An earlier Macintosh game called World Builder, by Silicon Beach Software, allowed players to create their own levels or games and share them with others. He had seen some of these World Builder games on FTP sites; it seemed like a good idea to let Glider players create and share their own content, too.

World Builder.

The timing could not have been better. America Online (AOL) emerged at around the same time as Glider 4.0, which was the version made for Casady & Greene. Glider houses had very small file sizes, so they could be uploaded and downloaded quickly from AOL at dial-up speed.

From here, a thriving community of modders grew up around the game. People evidently loved the idea that they could make a game of their own using the simple editor. The ingenuity of some of them surprised Calhoun, who did his best to download and play them all (until the sheer volume became overwhelming). One house, created by Ward Hartenstein, could be played in its entirety without touching a single key. Like a Rube Goldberg machine or the auto-Mario levels that have become popular on YouTube, the house played itself in a breathtaking display of artistry.

The house editor came with a huge cost of time, however. The decision to include it with the game meant that Calhoun needed to add sanity checks and considerable polish so that it was usable by a mass audience. It would not do to have a candle that sucks a Glider towards its flame; every object required similar checks to ensure players could not break the game. Layering a highly polished user interface on top of the editing functionality was essential to the accessibility of the editor. The work required to do all of this, as far as Calhoun can recall, actually exceeded that which he put into the game itself, even though Glider 4 used none of the code from Glider 3.

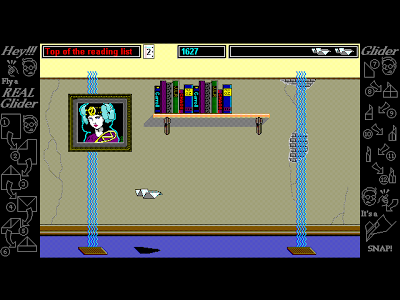

The Glider 4 Room Editor (left) and default house (right)

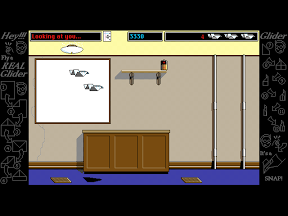

Glider 4 was a major departure for the series, and not just because of the editor and commercial release. Both the introduction of power-ups and the shift to a 16-color palette contributed to a significant change in tone. The game now felt somehow darker and edgier, like the house secretly had it in for you, and all was not well in the magical Glider-land. Hitting a switch could now cause a big chain reaction or radically alter the dynamics of a room. Foil (for protection) and rubber bands (for player-fired projectiles) were added to differentiate the game from its shareware predecessor, but they had an inadvertent knock-on effect. The rooms became more claustrophobic, fraught with danger, as though you were leaving the playground and entering a war zone.

Yet Glider retained its charm. To save memory, Calhoun limited the game to 16 colors instead of the 256 that newer Macintoshes supported. He tried to make up for this limitation by using a graphics technique called dithering, which involves scattering different colored pixels in an image to give the appearance of an intermediary color. Most often, he used a dithering pattern that consisted of two colors -- usually grey and a primary or secondary color -- alternating in a checkerboard pattern.

This resulted in a muted, desaturated color. Different shades of grey provided variations, such that the 16-color palette could be used to produce far more than 16 colors. This, quite deliberately, led to a frumpy and dinghy-looking house -- similar to that in which Calhoun lived at the time.

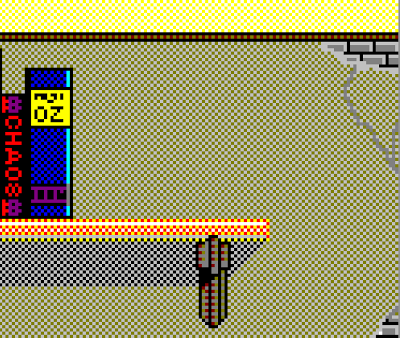

Pattern dithering in Glider 4 (left) and the Windows port (right)

Glider 4 was successful enough to warrant a Windows port. Unfortunately, the game looked dated by the time it was ready for a PC audience, and publisher Casady & Greene was unsure how to market to Windows users. As a result, the game failed to make a splash; the Glider phenomenon remained confined to the Mac.

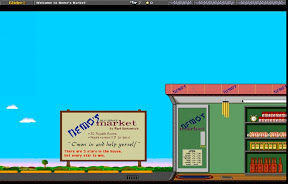

Glider PRO arrived on the scene in 1994, around the same time as the Windows version of Glider 4. The tone shifted again as support was added for outdoor environments -- rather than feeling claustrophobic and dark, Glider PRO felt open, bright, and laid-back.

The change came because Calhoun was feeling restricted by the Glider formula. “I was beginning to feel perhaps like someone who has been cooped up too long watching TV or otherwise wasting their life away," he says. "So I literally threw the windows open.” The prize was no longer escape; it was collecting all the “stars,” which were scattered throughout the house (although “house” had become a much looser concept).

The resulting game had incredible variety. There were tree houses, graveyards, sewers, castles, an art museum, a grocery store, a space station -- even the Titanic. Calhoun enlisted the help of several of the community’s best house designers to make Glider PRO the deepest, most definitive version of the game. One house, Slumberland, was co-authored by Calhoun, Paul Finn, Steve Sullivan, and Ward Hartenstein. The default house in Glider PRO, it included a whopping 403 rooms, and was the closest Calhoun ever got to fulfilling his dream of a huge house with thousands of rooms.

The community embraced the game, diving in to the improved modding tools. Hundreds, perhaps thousands of houses were created, with many taking advantage of the new option to load different artwork. Two e-zines sprung up, each lasting a couple of years, while other fan websites and newsletters developed (and survived) well into the next decade.

Custom "houses" for Glider PRO

Some have suggested that Glider lost much of its charm in the transition to PRO, however, and Calhoun is inclined to agree. He suggests that the expanded scope came at the cost of a “quiet domesticity,” which was core to the original game’s charm. But he is (currently) unable to take a new stab at the “definitive” Glider -- even if he wants to -- because of commitments as a programmer at Apple (he left the games scene many years ago, after his other games failed to match Glider’s impact).

![]() The Mac gaming scene -- along with the Mac itself -- has changed and reshaped considerably since the arrival of OS X at the turn of the century. Games like Glider have become rarer as the Mac audience grows more fragmented. Little indie games are seldom seen at trade shows alongside the big commercial apps, and the Mac seems to be losing both its underdog status and its tight-knit community. Calhoun readily admits that the heady days of shareware, which catapulted Glider into the limelight, are long over, while the excitement has shifted to Apple’s iDevices.

The Mac gaming scene -- along with the Mac itself -- has changed and reshaped considerably since the arrival of OS X at the turn of the century. Games like Glider have become rarer as the Mac audience grows more fragmented. Little indie games are seldom seen at trade shows alongside the big commercial apps, and the Mac seems to be losing both its underdog status and its tight-knit community. Calhoun readily admits that the heady days of shareware, which catapulted Glider into the limelight, are long over, while the excitement has shifted to Apple’s iDevices.

But for many of its fans, Glider is, was, and always will be the quintessential Mac game -- charming, friendly, unique, and somehow magical. It shaped John Calhoun’s life and, I’m sure, many others.

This article was originally published on MacScene and is based on an interview with Glider's creator, John Calhoun, which is available in two parts: part 1 and part 2.