On September 13, 1985, for the first time, a tiny plumber single-handedly saved a princess...and the console-game industry. Super Mario Bros. was originally released 25 years ago today in Japan, bundled as a launch title for the Nintendo Entertainment System, and it changed everything for an entire generation of gamers.

I came a little late to the Mario party. Home gaming was pretty much dead to me for a lot of years after playing both E.T. and Pac-Man for the Atari 2600, a double-whammy of suck potent enough to turn the Pope into a bitter unbeliever. If that was the best anyone could do, thought the young and vengeful me, the Video Game Crash of '83 counted as a divine wind, sweeping away the unworthy developers, publishers, and systems. My brilliant plan involved sinking money into the local arcades, where at least the games worked. I didn't even touch an NES until I ran into one by accident, crashing with the gang at my then-girlfriend's house. She fired it up to show us, in her estimation, the best video game ever conceived by man: Duck Hunt.

After an hour of taking turns annihilating waterfowl, she mentioned offhand that the cart also contained this game called Super Mario Bros.

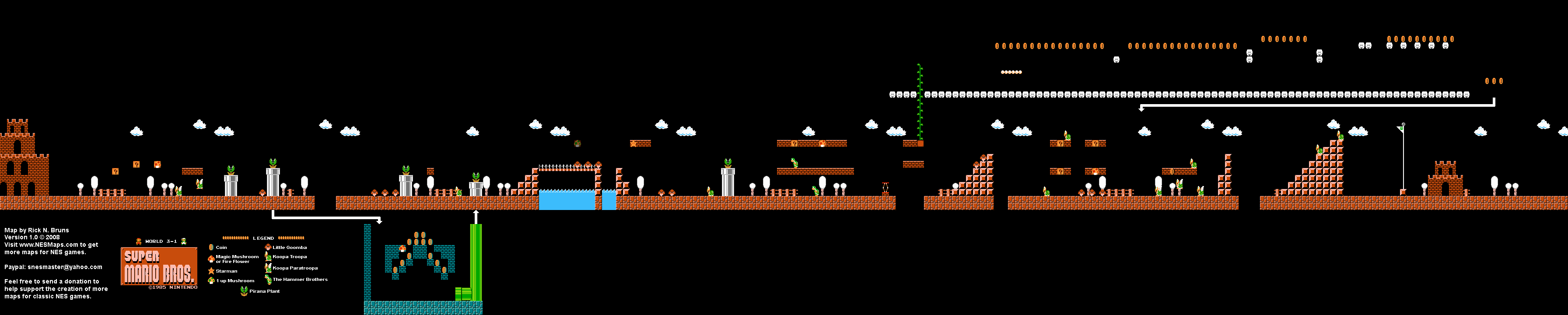

It took a while to really hit me, how truly special this game was. Had it been released in the 21st century, Super Mario Bros. would still rate as a great game. Back in the '80s, it was a revelation. This was the era before power-ups, hidden areas, hidden items, or multiple levels became standards. Super Mario had power-ups, hidden areas, hidden items, and multiple, brilliantly designed levels that paced challenges to rewards beautifully. Mario's creator, Shigeru Miyamoto, built a consistently good, constantly evolving experience unlike anything I'd ever played before-- unlike anything anyone had ever played before. It's pretty amazing when you consider Miyamoto didn't have a reference point for how these things should be done. He created the reference points for others.

The funny thing is, so much had to go wrong to reach that point. Nintendo of America had to be on the brink of financial ruin, prompting Nintendo of America CEO Minoru Arakawa to beg Nintendo of Japan CEO Hiroshi Yamauchi -- his father-in-law -- for a rescue operation. Nintendo had to pursue and lose the license to make a Popeye game, forcing Miyamoto -- on his first project as lead designer -- to recast the cartoon's famous love triangle. His new game, Donkey Kong, had to fit within the hardware limitations of failed arcade title Radar Scope, because 3,000 of that game’s cabinets were gathering dust in NOA's warehouse. Their landlord, a man named Mario Segali, had to burst into a meeting to demand “back rent” just as Arakawa was trying to think up a better name for Jumpman, Miyamoto's workman hero.

Miyamoto designed “Jumpman” to be his go-to character, a sprite he could fit into any game as needed. A boxing referee. A face in the crowd. A villain to defeat. The little carpenter already had quite a resume by the time he got his first headliner (and a change of profession, at the suggestion of a colleague), Mario Bros., Miyamoto's first shot at a multiplayer game. A simple palette swap provided Mario with an instant sibling. Stories vary on how Luigi got his name, from a play on the Japanese word for "analogous" to a pizza parlor near Arakawa's office supposedly called Mario & Luigi's. Either way, Luigi wouldn't get his own design or personality until he was grafted onto Mama from Yume Kojo: Doki Doki Panic, the game unceremoniously converted into Super Mario Bros. 2 for the American market.

And minus that one aberration, the plot of every Mario game hasn't moved an inch off the template Super Mario Bros. created. Our hero is summoned by Princess Peach/Mushroom/Daisy, often using the lure of free cake, only to witness her kidnapping at the hands of Bowser/King Koopa/Wario. That sameness earns some justified criticism, but who honestly wants to change it? In my world, you don't play Mario for the story. A deeply layered plot would only distract from what truly makes these games great: the purity of the gameplay.

In a field crowded with destructible environments, headshot kills, and variable gore levels, Mario remains that one dependable harbor where a game is simply fun for fun's sake. Super Mario Bros. became the last time Miyamoto could go completely hands-on for every aspect of a game under his direction. His responsibilities overseeing Nintendo development studio R&D4 just made too big a demand on his time. So yes, some nostalgia exists for that more innocent time, but it's also tough to overstate everything this one game did. It took the brothers Mario away from construction sites, out of the sewers, and into the Mushroom Kingdom. It resuscitated the game-console industry in America after critics declared it DOA. It kick started an entire genre and introduced millions to their new hobby. Or, in my case, re-introduced me to my love of gaming.

The platformers that followed have done more, and done it better, but they can all trace their lineage directly back to this day, 25 years ago. Twenty-five years from now, we'll still remember. This is where it started. This is why, virtually anywhere in the world, Mario means Play.

Happy birthday, boys. Enjoy your cake. You've earned it.

Check out Nintendo's own video celebrating 25 years of Super Mario Bros.