So much of life is cyclical. Eddie Izzard said it best when he was talking about fashion::"'over here you've got 'looking like a dickhead', then another third of the circle's sort of average looking, then you've got cool, cool, hip and groovy... and looking like a dickhead'. There are pieces of art, literature, movies and occasionally games that straddle that International Quality Line between amazing and awful, and Flower Sun and Rain is the best example.

Now, I'm not saying FSR falls into the 'so bad it's good' camp- playing the old Digital Pictures CD games- Sewer Shark, Night Trap and the like, you might have a hearty ironic laugh at the production values and the acting, but if you actually enjoy the games for their actual worth, or think they contribute anything meaningful to the medium at large, you might need your head checked.What this 2008 DS release does though, is artfully (or clumsily depending on perspective) walk the tightrope between genius and madness.

Even the very existence of the game is a mystery. Originally a Japan only PS2 release in 2001, it garnered mediocre reviews and slow sales. Seems hardly the sort of thing that would warrant a remake on DS, much less a European and American localisation, but it rings true of Goichi Suda and Grasshopper Manufacture's reputation of marching to the beat of their own drum.

At first glance, FSR appears to belong to the point and click adventure genre, something which has had a resurgence over the last couple of years thanks to various DS, iPhone and XBLA remakes of Monkey Island, Broken Sword and the like. Main character Sumio Mondo must talk to residents of the titular hotel and surrounding area for hints to puzzles. Where a point and click adventure requires puzzles to be solved within the games environments, however, puzzles in FSR are more abstract, requiring you to derive numerical solutions to word, logic and maths related problems. The main items in your inventory for the game are a real world notebook and calculator as you puzzle out a vague question (and subtle option menu hints) to find you must calculate the volume of a dodecahedron to advance, for example.

This abstraction of the gameplay mechanics from the game scenario itself means it's up to the writing and characters rather than the player to move the story along. And what a story it is. Almost impossible to spoil on account of being so difficult to comprehend in the first place FSR is deliberately surreal and obtuse, finding some similarities with writers like Haruki Murakami (specifically echoing 'Wind Up Bird Chronicle' and 'The Elephant Vanishes')at its best. Ultimately, though, narrative runs out of steam and Mondo, baffled, leaves the tropical setting of the game at the end no more the wiser as to what's going on as when he started.

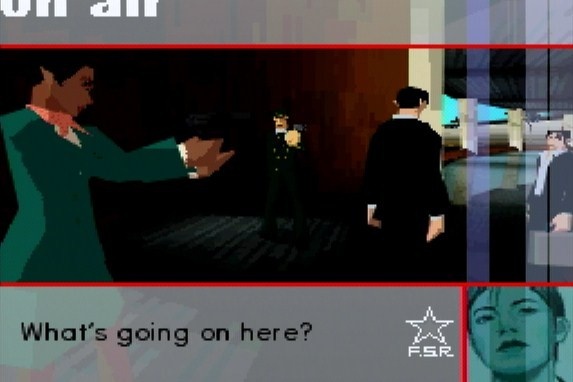

FSR is really a comedy, then, and Mondo is a fantastic lead. Thanks to the game's technical failings and art direction, Mondo's face appears reasonably featureless, and being a physical blank slate makes it all the easier for you to project youself on him. Mondo voices his confusion at the plot and frustration at the game mechanics as often as you do., and as I wrote recently, the game frequently reaches through the fourth wall, a trait typical of Suda's design. Early on, Mondo comes across a meddling child who constantly derides the game. 'Our polygon faces look nothing like our 2D art!' whines the kid , and when threatened with a clip around the ear warns that child abuse would mean a mature rating and no sales. With no recourse and threatened with the whole secret of the game being unveiled, Mondo retruns to his hotel room, moaning that 'with no sense of mystique, this game would be nothing but a collection of obscure in jokes'.

A lot of those in jokes are directed in such a way as to leave the player the butt, which means a lot of its laughs are attained through gritted teeth.With a nod to constantly overlooked backtstory and audio logs in games, FSR forces you to read through backstory in order to uncover puzzle hints in the game's MacGuffin of a mystical island brochure. Arguably something of an alternate reality game trait, the brochure would have existed better as a physical handbook or a website, but in game is a pain to navigate (a fact that, yes, Mondo complains about).

He also frequently complains about the walking that has to be done. Backtracking is the bane of an adventure game's existence, and Suda rubs this point in by not only forcing you to walk long distances in the game but counting the amount of steps you've taken and awarding bonus unlockables for doing so. Unlocking all the game's items can be done by walking a huge 51000 (Goichi Suda=Suda 51...51000... Heh....Heh) in game steps- if frustration hasn't lead to the snapping of your spirit (or stylus) before then.

Mechanically a mess, ugly, with a nonsensical story arc, and arguably worse, knowingly this way, FSR's frosty critical and commecial reception is easy to see, and probably justified. Yet through its well rounded characters, thought provoking nature, and simple charm was a game that kept me playing until its conclusion, and had me enjoying it. It's not for everyone. It's not for many people. In fact it's undeniably a bad game. It is, however, probably the very best bad game ever made.